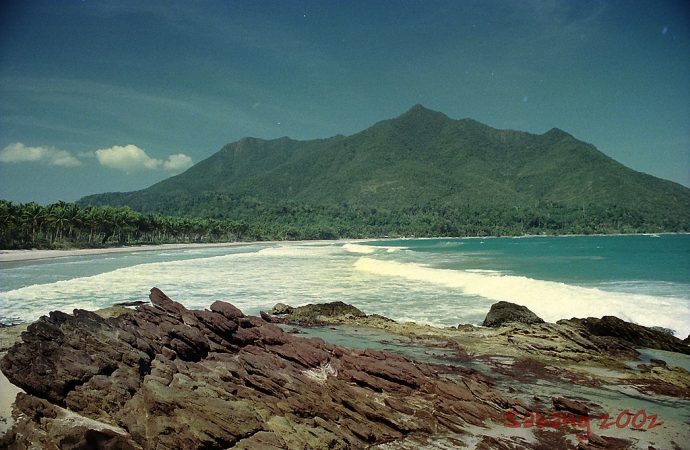

Sabang is a coastal town on the Philippine island of Mindoro. Until the early 1980s it was a small, poor fishing village, but thirty years later it had become a popular site for Western male tourists, seeking scuba diving during the daytime and commercial sex in the nighttime. The town now hosts approximately 5000 inhabitants. Today, Sabang is identified by the tourists, international travel guides, and local Filipinos as a sex town.

Sabang is an international place. Among the local Filipinos with pre-tourism ties to the town, Western foreigners live in Sabang, permanently or semi-permanently, domestic migrants seek work within the tourism sector, and foreigners, mainly from Europe, Australia, and, more recently from South Korea, come for vacations.

Tourism is a main vehicle through which many interactions between people occur. People from all parts of the world meet through tourism, yet anthropologists have remained somewhat impassive to the occurrence. But anthropologists have studied tourism. One of the most common if not the most common approach is to highlight the effects tourism has had on local communities. In Sabang, the development of a commercial sex scene catering to international tourists has had blatant effects.

How commercial sex changed Sabang

Throughout the process of researching tourism in Sabang, I asked myself: what is it like to live in a place which has become an international sex tourism town? Catholic-based moral and gender values and roles, as emphasized by my local Filipino informants as highly important, seemed to contradict what was going on around them. How can people condemn commercial sex as ‘immoral’ but going on living their everyday life in the midst of it?1

As an anthropologist I sought to answer these questions by two of fundamental principles within the discipline: that of ethnographic fieldwork and that of the notion of human practices as deeply embedded within local social and cultural contexts – and so is also sex tourism. Over a period between 2002 and 2015, I spent approximately 18 months in Sabang and I learned how embedded tourism had become in Sabang.

Commercial sex and foreign tourists’ entitlements to pay for sex with young Filipinas seem accepted. A majority of my Filipino informants highly depend of the sex trade in Sabang; sex is what attracts the tourists there. Not only the ones directly involved in the sex trade, like sex workers, bar and hotel owners, and DJs, rely on it, but also people who in their daily lives have little to do with commercial sex express dependency, such as beach vendors, seamstresses, or carriers of scuba-dive equipment, as they realize that they are dependent on tourism, which in Sabang translates to sex tourism.

[su_quote]The host-societies are not mere passive receivers of global, dominant sexual desires; they are places in which people live their everyday lives[/su_quote]

At first, local Filipinos’ logic towards the sex scene seemed contradictory: they condemn it as immoral but condone the practice. How does this work? Local Filipinos distance themselves from commercial sex, through various strategies, for example by negotiating identities and clearly defining who is an insider and who is not”.

Negotiating Identities

The go-go bars in Sabang, like other places in the Philippines and Southeast Asia, have an air of “open-endedness”2. In Sabang, this means that as a client you pay the sex worker for the company of the whole evening rather than for an hour or a specific sexual service. Sex workers and their clients often engage in short (or sometimes longer) relationships, where socializing as a couple is a significant part. This is an institutionalized practice, and ‘company’ (though not sex) is provided by specific establishments, which are registered, taxed and monitored.

The payment for sex is however not a subject of municipal control but is agreed upon by the sex worker and the client. The status of commercial sex (or prostitution)as nationally illegal is thus conveniently bypassed by the establishments, by ‘merely’ offering company and letting the sex worker and client deal with the illegal aspects of their relations on their own. As commercial sex is illegal, and no public records prove that ‘prostitution’ is taking place people can downplay the immoral connotations of Sabang’s nightlife.

[su_quote]The sex workers are easily identified as outsiders in Sabang. They come from other, poorer parts of the Philippines[/su_quote]

Outsiders and Insiders

The sex workers are easily identified as outsiders in Sabang. They come from other, poorer parts of the Philippines and they need money (though other reasons for entering the commercial sex scene exist, including escape from abusive relationships, personal sexual drive and desire, and wanting to meet potential foreign husbands). Local women and their families rarely stand without an income, thus the financial push-factor is often minimal. And more significantly, local women are banned from working as sex workers in order to protect the honor of their families and that of the local community.

Sabang is a site for foreign tourists and it is too expensive for domestic tourists – their presence is negligible. Sex tourists are thus also easy to spot as they are foreigners. Filipino local men are prohibited from entering the go-go bars. This rule is however circumvented, in particular by Filipino local men of power and prestige who may enter the establishments. Also, local men may come to an agreement with sex workers on a private initiative. But the rule of thumb is that local men do not, at least officially, engage in commercial sex.

The sex scene in Sabang is thus constructed on the premise that it is something ‘from the outside’ – the ones that demand it as well as the ones who provide it. In addition is the ‘need’ for commercial sex naturalized in terms of male sexuality (as an innate drive) which is combined with the logic of tourism as providing an outlet for this need. Sex becomes commercialized through international tourism, and Sabang becomes merely a place for such activities.

Sex Tourism – Controlled Ambiguities

Commercial sex draws attention to issues of gender, race, sexuality, power and equality, commercialization of sex, and global patterns of gendered tourism. Sex tourism is a topic of heated debates and negotiations also in Sabang, one of the places in the poorer countries to which Western men travel in pursuit of commercial sex.

The host-societies are not mere passive receivers of global, dominant sexual desires; they are places in which people live their everyday lives – and that they may be environments which have complex social relations, where people may hold sometimes contradictory ideas of how the (sex) tourism scene should be shaped, and where the locals in various ways do their best to make sense of living in the midst of a vibrant international commercial sex scene.

There is no local agreement regarding permitting or banning commercial sex in Sabang. Some argue that sex tourism is injurious to local morality and that all establishments “of ill repute” (as it is formulated in a proposition to the Municipal Council) should be closed down and sex workers expelled from Sabang. Others maintain that sex tourism is crucial to the local economy and that any attempts to curb it would lead to dramatic decrease in tourist arrivals. It’s no surprise that people who are more dependent on the activities of the night emphasize the community’s dependency, while those more removed from sex tourism express more critical stances.

Sabang is a place of a wide range of relationships, where people from different parts of the world, with different notions of gender, sexuality, and morality co-exist. Although there is no absolute agreement regarding the future of the local commercial sex scene, most people, be it Western foreigners or local Filipinos, have a vested interest in maintaining it.

Elina Ekoluoma is a Cultural Anthropologist and investigates international tourism to the Philippines. Write her at Elina.Ekoluoma@antro.uu.se

References:

1In my Ph.D. thesis Everyday Life in a Philippine Tourism Town I take a broader approach and situate these questions in the context of international tourism, local responses to tourism, in particular with regards to issues of social hierarchies and maintaining socio-cultural boundaries.

2This term is generally accredited sociologist Erik Cohen (see for example 1993 “Open-ended Prostitution as a Skilful Game of Luck: Opportunity, Risk, and Security Among Tourist-oriented Prostitutes in a Bangkok soi.” In: Tourism in South-East Asia. M. Hitchcock, King, V. T. & M.J.G Parnwell (Eds.). Routledge: London. pp. 155-178)

Image Credit: jackylim [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons