“Bees know best,” beekeepers in Bosnia-Herzegovina tend to say. Keen observers of hives, Bosnian beekeepers take bees as knowledgeable beings. The bees, they say, concoct complex hive substances, from honey to wax, that baffle research scientists. Bees can tell when the weather is about to change or how long a lull in a storm will last. Most importantly, they know how to live well: working cooperatively for the sake of the hive, while gently tending the wider world. In the local language of apiculture, bees are said to live in a kin-based “society” or “collective” (društvo in Bosnian-Serbian-Croatian) wisely held together by the “mother” (matica). Curiously, the bees are said to die (umiru) like humans, whereas other animals and insects perish (uginu, crknu).

What difference does it make how we think and talk about bees—whether we say that they “know” how to live well or are merely operating on instinct?

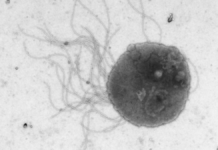

Honeybees at the countryside

I have tackled this and related questions since 2014 as I have investigated local apicultures across Bosnia-Herzegovina. As an anthropologist, I have worked closely with beekeepers in the field and spent the year of 2017 immersed in local beekeeping practices. I followed mobile beekeepers as they took bees to forage in the wild, observed them collecting hive products and herbs to make medicine, and lent them a hand in seasonal and daily tasks. Along the way, I established a small apiary, and beekeeping grew into a family passion. My sister, Azra Jasarevic, an independent filmmaker, captured the fieldwork experience on film; our mother, Zumra, planted bee-friendly plants and kept the records on our apiary. Even our cat, Pepe, joined us by the hives to watch us work.

Small-scale apiaries dot the cities and countryside of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Many beekeepers take bees to forage away from urban and industrial landscapes. In pursuit of clean and diverse nectar and pollen, they often travel to former frontlines blasted by the 1990s war. Strewn with mines, these expanses of fields, forests, and nearly abandoned villages are overgrown with myriad weeds, herbs, and blooming trees—from fragrant linden to thyme. While these post-conflict zones, unsuitable for industrial agriculture, may seem commercially “useless,” the bees and their keepers value the biological diversity of the new wildness (divljina), unhindered by chemical herbicides or monocrops. Making honey from the former frontlines, bees and their beekeepers are repurposing a land deeply marked by recent genocidal bloodshed.

Divine medicine

In North America, honeybees (Apis mellifera) are primarily seen as pollinators—whether they are employed in cash-crop farms, like the almond orchards of California, or kept by hobbyist beekeepers or organic apiarists. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, bees are kept primarily for the sake of their medicinally valuable products: honey, pollen, propolis (an amber-hued, gluey substance that bees use to seal and clean the hive), wax, and the “bee mother’s milk” (matična mliječ), known in English as “royal jelly.” Honey, besides being sweet, contains minerals, metals, and enzymes; pollen is rich in protein and vitamins; propolis is known for anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal action; and royal jelly is extremely rich in amino acids. Used alone or in combination with medicinal herbs, apian products are used for medical complaints ranging from skin and digestive disorders to liver and heart conditions.

It is the medicinal efficacy of hive products, in particular, that the local people emphasize when claiming that bees are knowledgeable. Islamic sources describe these creatures as divinely inspired with knowledge. Hive products, devout Muslims and devoted beekeepers say, cannot be reproduced in any human lab; their recipes are the secrets kept between the bees and al-Aleem, “The Knower” (one of God’s names).

A world without honeybees?

Over the three years that my sister and I spent researching local apiaries, we grew ever more deeply attached to the bees—and ever more worried. We saw two extreme weather events bring them to the brink of starvation. In 2014, in the wake of a cyclone that hit southeastern Europe and Central Europe, floods and landslides drowned hundreds of small apiaries while the continued rainfall ruined forage for the rest of the year. In 2017, the so-called “Lucifer” heat wave that swept Europe also ruined forage, forcing beekeepers to feed the bees with sugar syrup.

Extreme weather, climate change, pesticides, and new diseases are contributing to a global emergency for honeybees, while several other species of bees have now been listed as endangered. The often-heard question, What would happen if honeybees disappeared? can no longer be asked as if the only thing at stake is the food on our plates, which would be rather bare without pollinators. Honeybees’ endangerment intimates something more immediate and daunting: Life is becoming untenable on our planet.

Researchers around the world share an appreciation for honeybee behavior: from their social language to their ability to remember forage sites and anticipate the timing of nectar flows for different flowers. But few modern scientists would grant bees “intelligence” or “knowledge.” The typical scientific view is that while the hive, as a social organism, makes first-rate intelligent decisions, each bee is merely a dumb, small-brained, instinct-driven cog.

But what if honeybees actually do “know” how to live well? Is there something we could learn from them? Could we take instructions from insects on how to gently tend damaged landscapes? Could we learn to transform the world we encounter into sweetness to share with our fellows? Perhaps we should think about the Bosnian folk—and Islamic—idea that humans and bees have something vital in common: They are alike in facing death.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.

Larisa Jasarevic is an anthropologist at the University of Chicago who studies everyday life in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Azra Jasarevic shot the video that accompanies this article. She is a graduate of the International School of Film and Television, San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba.

Image Credit:Andreas Trepte; Wikimedia Commons