A few days after giving birth at her home in southeast Australia, Emily Burns sat in her yard and watched as her husband and 2-year-old son dug a hole. In her arms, she cradled her sleeping newborn; beside her was a small container holding her placenta. It was a beautiful October day in 2008.

When the hole was big enough, Burns gently laid her still-sleeping baby onto the soft grass beside her to pick up the container. She walked over to the hole and placed the placenta inside. She then paused, resting her hand on the earth, and silently acknowledged what the placenta had given her. “I felt emotional, bestowing the thanks for my beautiful healthy baby on this organ that had been grown just for that purpose,” she recounts.

When it was time to plant the peach tree atop the placenta, Burns hesitated, feeling as if she was “saying goodbye to something very special that would not return.” The trio then packed handfuls of earth in the hole around the tree until it was filled. Finally, she gave her baby a kiss.

Burns’ ritual was much more ceremony than is afforded to a placenta in most Western cultures. In countries where the childbirth process is highly medicalized, the placenta is typically whisked away to the incinerator. Recently, however, there has been some pushback: Maternal placentophagy—a mother’s consumption of the placenta after giving birth—has become an increasingly popular practice in wealthy, developed nations. Proponents, including celebrities and social media influencers, insist—based on anecdotal evidence—that it can boost new moms’ milk supply and mood levels, even going so far as to say it can fend off postpartum depression.

Thus far, researchers have been unsuccessful in validating these claims in large-scale studies—but this newfound Western interest in placentas has helped propel investigations into the varied cultural practices surrounding the placenta. Anthropologists are uncovering myriad practices for handling this organ. Because traditional cultures have long recognized and revered its power, the placenta is treated with great respect throughout much of the world, often disposed of in solemn ceremonies. Inspired by those rituals, more mothers in the West, like Burns, are finding ways to appreciate an entity that modern medicine has dismissed as medical waste.

A magical organ

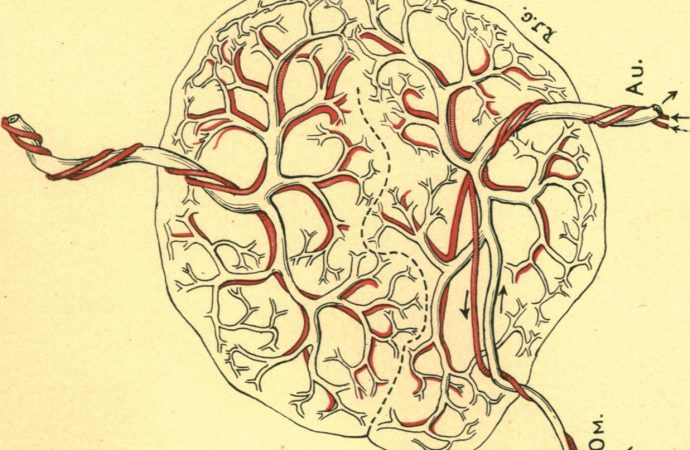

The placenta is a magical organ. It’s a 1-pound frisbee-like mass of tissue that, together with the umbilical cord, brokers the sharing of resources between mother and fetus, maintains the uterine environment, filters out toxins, and disposes of waste. It’s the body’s only temporary organ, conjured by an embryo and expelled when its job is complete. Blood vessels spread across its surface like the wide, billowing branches of a tree.

In 2010, medical anthropologists Daniel Benyshek and Sharon Young, both at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, set about analyzing the traditions of 179 cultures for handling of the placenta. They found that among the 109 communities that define culturally appropriate placenta rituals, there were 169 disposal methods, including burial, incineration, intentional placement in a specific location, or hanging in a tree or structure. When Burns chose to bury her child’s placenta under a tree, she participated in one of the most common disposal methods. In many cultures, the tree is thought to act as a protector of the child; alternatively, the tree’s health could foreshadow the child’s well-being and prosperity.

Burns knows that fact well. She is not just a practitioner of placenta ritual. She studies home-birthing and placenta-disposal practices among modern Australians as a researcher at Western Sydney University’s School of Social Sciences and Psychology. Becoming a mother sparked Burns’ fascination with placenta rituals and other elements of spirituality in childbirth.

“Around the world, various traditions, customs, rituals, and beliefs surround the placenta,” Burns wrote in a 2014 paper in The Journal of Perinatal Education. She noted that scholars believe these practices may release some of the anxiety that often accompanies labor, birth, and new motherhood.

Click on the red dots to explore a sampling of placenta rituals from around the world.

Placenta: a living being, a guardian angel

The placenta is commonly believed to be a child’s living relative: several cultures refer to it as a mother, sibling, or grandmother. “Across the Americas, the placenta is treated reverentially,” wrote Patrisia Gonzales, an assistant professor of Mexican American studies at the University of Arizona, in her book Red Medicine: Traditional Indigenous Rites of Birthing and Healing. “For many Indigenous cultures, the placenta is a living being.” Some other cultures believe in a sort of twinning of child and placenta. In Ancient Egypt, the placenta was considered by many to be a child’s secret helper. Some Icelandic and Balinese cultures see the placenta as a child’s guardian angel.

In many traditions, people believe that improper handling of the placenta will affect the fate of the mother and/or child—or that the placenta’s condition is an omen for the child’s abilities or health. Rituals must therefore be performed exactly and can be quite involved, requiring that the placenta be washed in special liquid, wrapped in certain fabrics or plants, placed in a specific vessel, and buried or set in an appropriate location.

But of the many rituals investigated by anthropologists and social scientists more broadly, one is notably absent from the list: the increasingly trendy practice among Western women of eating the placenta.

Eating the placenta

Benyshek’s interest in placentas was piqued in 2008 at a departmental brown-bag lunch presentation at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. There, a prominent local placenta encapsulation specialist described how she prepares placenta for a mother’s consumption. The organ, she explained, is typically steamed, dehydrated, ground, and placed into capsules.

Curious about academic research on the practice’s history, Benyshek approached the speaker after the presentation. What he learned next about placentophagy surprised him. “I asked her what research was being done into it and she said none. I couldn’t believe it. There was no look at traditional cultures,” he says.

That absence inspired Benyshek and Young’s 2010 cultural analysis, which examined a range of rituals but found virtually no evidence of mothers regularly consuming their own placenta. Granted, they only looked at 179 cultures: “It was a representative sample, but it’s not an exhaustive list,” Benyshek says. But their data suggest that, if anything, many cultures avoid eating the placenta. (Indeed, some communities believe that the mother or child will be harmed if an animal, for instance, consumes the placenta.)

Although a few cultures do have long-standing beliefs that the placenta can be an edible remedy, the practices rarely resemble modern maternal placentophagy. For example, in some, pieces of the umbilical cord or placenta are dried and later fed to the child as a treatment for illness. And in traditional Chinese medicine, which placentophagy practitioners point to as the source of their practice, “it is not a mother ingesting her own placenta, it’s always another person’s placenta,” explains Benyshek. “Also, it’s not prescribed right after birth, though it is said to treat low milk supply,” he adds. In addition, traditional Chinese medicine sometimes prescribes dried placenta for chronic cough, liver problems, and male impotence.

There is perhaps just one line of logic that suggests the practice of a woman eating her own is, in a sense, ancient. Among almost all mammal species on Earth besides humans, birthing mothers eat their own placenta. It’s possible, then, that early humans had, at some point, an animalistic impulse to devour the placenta—fresh and raw—just after giving birth.

Benyshek believes that tendency would have ended after our species discovered fire, an innovation that would have regularly exposed humans to toxic smoke and ash. Since the placenta acts as a filter, wherein toxins accumulate, the organ was an increasingly poor choice of nutrients.

A risky endeavor

Today, in fact, ingesting one’s placenta remains a potentially risky endeavor. “Placentas are often colonized with bacteria. Many are infected. As a general rule it’s best not to eat something that is potentially teeming with bacteria, many of which may be pathogenic,” wrote Jen Gunter, an OB-GYN at the San Francisco Medical Center, in an opinion article in The New York Times last year. Gunter, who has fielded requests by mothers who want to keep their placenta, noted that the organ can carry traces of arsenic, mercury, and lead. She also worries about how the reproductive hormones in placentas could affect new moms.

In 2017, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned against the practice of ingesting encapsulated placenta after an infant developed a life-threatening infection. The baby’s mother consumed her own encapsulated placenta, not realizing that it contained group B streptococcus bacteria. The baby then contracted a strep infection that developed into sepsis.

Consuming the placenta may not be advisable—nor may it have the deep cultural roots that some adherents describe—but studying the treatment of the placenta has led researchers like Burns and Benyshek to question the dismissive handling of this organ in many societies.

A not-so-disposable tool for researchers

Western medicine is only just beginning to recognize the mysterious power of the placenta. For example, scientists are realizing how the expression of different genes in the placenta is linked to a number of pregnancy complications, including preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, miscarriage, premature birth, and low birth weight. In addition, since placentas are mostly made of the baby’s cells packaged inside the mother’s uterus, they are helping scientists to understand how cancer cells can similarly avoid being attacked by the immune system.

Benyshek likens traditional treatments of the placenta to those of a corpse after death; many cultures treat the placenta much like a miscarried fetus or stillborn child. Human remains are powerful—“potentially very dangerous, polluting, contagious,” Benyshek points out. They are therefore handled with attention and solemnity in many traditions. “It’s very striking when you contrast this [care] with how it’s treated in biomedicine: as biological waste.”

This idea of reclaiming the placenta from the status of biohazard or waste is a significant one. In New Zealand, the Maori use the same word for placenta and land: whenua. Traditionally, whenua were placed in hollowed-out gourds, earthen pots, or woven baskets, and then buried in a place of significance to return them to the Earth Mother. Later, British colonists dubbed the practice primitive and unhygienic. They regarded it as superstitious. The Maori began to treat the placenta as their European conquerors did: as medical waste. In the early 1980s, a small group of activists sparked a resurgence in traditional placenta burial, and it is now once again a common practice.

Burns has observed a parallel transition in her in-depth interviews with mothers in Australia who have had home births. “It was clear quite early in the research that the placenta was not an afterthought. … When you take away the medical context for birth, women and families are responsible for making some very specific and deliberate decisions about processes that are otherwise handed over to medical personnel,” Burns says.

Burns believes Western societies could benefit from adopting postpartum practices, such as intentional placenta disposal. There’s something to be said, she argues, for slowing down the transition to parenthood. “We can also learn the value in ritual, in a mourning ritual of burial in particular, as we might find comfort in a ceremony to say farewell to pregnancy as we move into motherhood,” Burns says.

As Burns’ baby grew, she says it felt very special to tell her child “these are your peaches” when they got a great crop from the tree planted over the placenta. When she looked out at the tree, she would feel a twinge of nostalgia for her child’s baby years.

Though Burns and her family have since moved, their old neighbor tells them the tree is still growing strong. Sad to leave it behind, they did try to dig it up and take it along, but it was just too heavy.

This work first appeared on SAPIENS under a CC BY-ND 4.0 license. Read the original here.

Image Credit: Reginald J. Gladstone / US / Wikimedia Commons