Travel writing is the literary narration of a journey by the traveller. But the genre is far bigger than its conventional definition. Travelogues express political commitments, states Debbie Lisle, who deals with the “connection of travel literature to the serious business of world affairs*”. More than just a literary genre with a political implementation, travel writing is a historical phenomenon. It defines, changes and expands the ideological decisions of the age, further constructing the history of the world.

The ambitions of an Empire

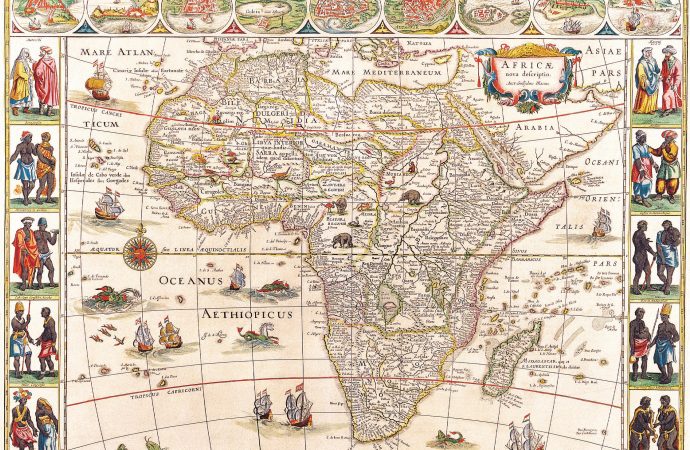

The genre has been central in the imperial ambitions of the Western world. It began by informing, and eventually luring, the capitalistic powers about the riches of the oriental world. Later, the genre allowed the explorers, missionaries and travellers to pave the path for the ‘humanitarian’ colonial agenda. The white man was always represented as a saviour, a selfless figure, while the “others” were savages in dire need of western intervention. The travel writings, rich in rhetoric artifices to construct the identity of places for readers, were powerful enough to establish the logic of Empire.

The power of travel writing texts is vested at different levels. First, it lies on a claim of authenticity: the structure, the tag of non-fiction and first-person pronouns ensure the readers they are reading the first-hand experiences of the author. Second, the claim of authority: the reader tends to move with the author and imagine the place and its people through the traveller. The text familiarises them with the foreign space, exactly the way the author – the sole authority and guide of the journey – wants it. Thus, the travel text becomes the parameter of understanding the foreign space; the traveller’s representation of self and the space of the travellee becomes the only ‘true’ picture of both.

Stereotypes in faraway lands

Travel writing solidified the constructed identities through the repetition of images of savage locals and saviour westerners. The travellers, explorers and missionaries observed, judged and represented the African space according to their set norms of civility, modernity and utility. They were the heroes of the journey and the space of the other was a foil in the plot of their narrative. The Victorian travel texts can be seen as a story of a courageous, determined and honest being moving through a place where everyone is trying to hamper his journey, unaware that he is on such a dangerous journey to save them. Those representations, much celebrated and sponsored by organisations such as Royal Geographical Society, became the symbol for faraway lands. For instance, the phrase “dark continent’, coined by Stanley, is still used as a symbol of Africa.

The stereotyped symbols became the identity of such places, specifically the orientals. The travel writing genre has not only been instrumental in describing the unseen lands; it has also influenced the ways through which the indigenous know and understand themselves and their land. For a significant time, the power of defining the indigenous cultures by western foreigners was undoubtedly within the colonial powers, which allowed the colonisation of knowledge production.

The colonial lens

The colonial tones and gaze prevailed: everything that was indigenous was referred to as occult, orthodox and uncivilized. The local people and their space were visited, seen, observed and represented through the western lens of civility. Africa is a perfect case study. The continent has been subjected to extensive representation by western travel writers through its people, landscape and culture. However, the absence of travel writings by Africans in and after the Victorian era, despite them being the companions of the colonial masters on their ‘difficult’ routes, highlights the level of the colonisation of knowledge and knowledge-producing structures.

The indigenous voices that defined Africa were either silenced or reduced to the auxiliaries. However, since the last decade, a shift in this power structure of knowledge production can be seen in African-authored travel narratives. For my Ph.D studies, I look at these travel texts and try to find out the ‘silenced’ voices of the Victorian era, with Central Africa as a case study.

Saviours and savages

I look at the techniques used by the genre to create an African identity. Particularly, I want to understand how cruelty is depicted and its role in creating the African stereotypes. The representations of Africa from the pre-colonial, colonial, and even post-colonial era are often constructed around a binary paradigm of dominant and dominated. However, little scholarship has examined how African travel writers have used these generic conventions when writing about Africa. Do they similarly set up paradigms of dominant and dominated, or imagine Africa as a zone for testing ‘civilisation’? Do they agree with western claims to power, which form an important part of western representations? How does their portrayal of landscape differ from their western counterparts and what arguments do they set up to validate or reject western opinions about ‘occult’ practices?

To understand this, I have analysed travel texts by African authors, in the hope of understanding how they identify themselves as a race in Africa and how do they connect to the African land. Through archival research, I am trying to find out the representations of Central Africa by Africans who were the indispensable part of European caravans in the late nineteenth-century.

The ever-lasting colonial nostalgia

Through the reading of these African authored texts from 1850 to 2000, I am addressing crucial questions: How do the African writers respond to the constructed identities of the British and the Africans? How and what change in identity has been developed and portrayed from colonial to post-colonial times? To what extent this change is validated by African-authored travel writing? How is the Western image of Africa in the twenty-first century based on nineteenth-century ideas for British authors as well as African authors? How is the representation of Africa, in particular, representations of cruelty and manipulation of memory by British travel writers, different from African-authored travel narratives? At this stage of my research, it can be argued that though the African authors could be seen grappling with westernised African identity and confronting the stereotypical image through their travel narratives, still the relevance and continuous presence of the colonial nostalgia cannot be ruled off.

This project will contribute to research on African travel writing as, despite the extensive scholarship on colonial and post-colonial travel texts, much less research has acknowledged the role of memory and cruelty in the genre. Furthermore, my research will offer one of the first studies of travel writing about Central Africa from African writers’ perspectives, joining an exciting body of new scholarship. It will examine the rhetorical strategies of power in both Western and African travel writing about Central Africa that constructs the (African) “Other” as cruel, occult and horrifying. The objective of this part of the study is to develop an argument about the varying meanings of ‘backwardness’ or ‘civilisation’ for African-authored narratives.

References:

Blunt, Alison. Travel, Gender, and Imperialism: Mary Kingsley and West Africa. Guilford Press, 1994.

Forclaz, Amalia Ribi. Humanitarian Imperialism: the Politics of Anti-Slavery Activism, 1880-1940. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Holland, Patrick, and Graham Huggan. Tourists with Typewriters: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Travel Writing. Univ. of Michigan Press, 2010.

*Lisle, Debbie. The Global Politics of Contemporary Travel Writing. Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012.

Siegel, Kristi. Issues in Travel Writing: Empire, Spectacle, and Displacement. Peter Lang Publishing Inc, 2002.

Thompson, Carl. Travel Writing. Routledge, 2011.

Youngs, Tim. The Cambridge Introduction to Travel Writing. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Image Credit: rosario fiore / Flickr