Greif and Tabellini, in Cultural and Institutional Bifurcation: China and Europe Compared, explore how cultures affect the development of different social organizations. They used the case studies of China and Western Europe during the pre-modern period to understand how their organizational bifurcation influenced their social and political development. The discussion aims to shed some light on the events that made possible the Great Divergence – known as the Industrial Revolution – and the reasons why industrialization took place in Britain and not in China, the richest country until the nineteenth 19th century.

Cooperation, society, and development

The author’s main claim is that Chinese society was dominated by kinship-based clans that fostered cooperation through inter-clan loyalty, while in Europe cooperation happened in cities, where the diversity of lineages and other identities demanded the creation of formal institutions that would universally enforce rules.

A clan (lineage) is a kinship-based formation where cooperation relies on intra-clan moral ties and reputation. They are often small and hence require little external involvement to enforce rules and norms. The low enforcement costs can give clans a competitive advantage and make them attractive. In this kind of society, cooperation usually occurs between kin members, which further fosters kin loyalty.

In China, the prevalence of kinship-based social structure is associated with Confucianism. After the Han Dynasty came to power, Confucianism which advocated for kin-based moral obligations as the foundation of social order replaced legalism that prioritized legal commitments. When the Han dynasty collapsed, China was split into smaller kingdoms. The areas dominated mainly by non-ethnic Chinese adopted Buddhism, which advocated for individual, monastic life, over Confucianism; However, soon after the ethnically Chinese Tang dynasty came to power and reunited China, they turned against Buddhism and destroyed thousands of Buddhist monasteries. Eventually, Confucian scholars formulated neo-Confucianism in a way that would be more appealing to the masses, while Buddhism was re-formulated to not undermine the importance of family and kin. As a result, by approximately 1000 AD, Chinese society was dominated by large kinship organizations.

The kinship-based social structure influenced the Chinese political system as well. Considering the large size of the Chinese empire, the ruling elites benefited from outsourcing some of their duties to clans. For example, clans had a responsibility to collect taxes, ensure the conduct of their members, and prepare them for civil service exams. Moreover, land could be purchased through the local clans.

In contrast with China, in Medieval Europe, the main form of cooperation took place in urban centers. Cities were attractive because of their large economies of scale. They were heterogeneous with different lineages and required external institutions for rule enforcement. Although moral obligations extended to an entire city population, they were not as strong as in the clan-based society. Therefore, formal agencies were necessary to ensure successful cooperation. The prevalence of cities as the main means of cooperation fostered a culture of universal morality and respect for institutional procedures.

Historically, Europe also had strong tribal societies, but the Church’s emphasis on generalized morality and changes in marriage practices enabled the existence of functioning multi-lineage urban centers. When the Germanic tribes, which were organized through large kinship groups, invaded the Western Roman Empire, the tribal system briefly returned; However, as the Church became more powerful and influential, a generalized morality replaced tribal obligations. The Church changed the marriage practices in a way that undermined the kinship system. For example, practices such as polygamy, concubinage, and marriage among kin members were discouraged, while women gained greater agency in deciding their marriage partners.

The emergence of cities with the absence of strong political and religious institutions in the 10th century created a need for more formal institutions in Europe. By the 10th century, both the Church and the States were weak. Cities, although secular, reinforced Christian dogmas, including moral obligations towards non-kin.

Foundation for the Great Divergence

The power of clans in China prevented the development of universal rules, while in European cities, reliance on formal institutions as an arbiter for ensuring cooperation created the economic and social foundation for industrial societies. The reliance on the clan enforcement of legal and social laws in China did not allow the creation of strong organizations that would regulate cooperation. Clan elders recognized that such agencies would weaken their power and therefore, opposed them. For instance, the Chinese state did not have a commercial code until the late 19th century because it relied on and encouraged intra-clan resolution of conflicts. Limited cooperation between clans was one of the reasons for the low urbanization in China between the 11th and 19th centuries, only three to four percent while in Europe it was around ten percent. Even in the Chinese cities, the clans dictated the rules of cooperation as opposed to the European self-governing cities.

Self-governing European cities fostered formal institutions and created a foundation that transformed a Malthusian into an industrial system more easily. The historical records show how the urban European centers evolved from “handshake” to contracts. Moreover, the cities invested in legal systems, including building legal infrastructure and educating judges, attorneys, scribes, and notaries. These assets enabled the transition from having voluntary judges who relied on customary law to formal legal codes and professional judges. Over time European cities became progressively heterogeneous and multi-lineage with strong administrative capabilities, such as collecting taxes and even fighting wars.

Although the authors do not explicitly link the different developments of Chinese and European societies and the great divergence, they present evidence that shows how in the eighteenth century, European cities were more suitable for industrialization than the Chinese clans-based society.

Grief and Tabellini’s article is a thought-provoking and original contribution to the subfield of scholarships in economic history that aims to explain the Great Divergence and the reasons why industrialization took place in Britain and not in China, the richest country until the 19th century. Many other academics have attempted to wrestle with the same question. For example, historian Christopher Isett, in China: the Start of the Great Divergence, writes that in England between 1600 and 1800, rising wages and labor productivity in agriculture created a market for manufactured goods, while in China, labor productivity was lower due to high population (98-100). Other authors connect industrialization to the black death, low energy costs, higher worker productivity, or even Protestantism.

References

Greif, A., & Tabellini, G. (2010). Cultural and Institutional Bifurcation: China and Europe Compared. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 100(2), 1–10. DOI: 10.1257/aer.100.2.135

Isett, Christopher. “China: The Start of the Great Divergence.” The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World. Ed. Stephen Broadberry and Kyoji Fukao. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2021. 97-122. Print. The Cambridge Economic History of the Modern World.

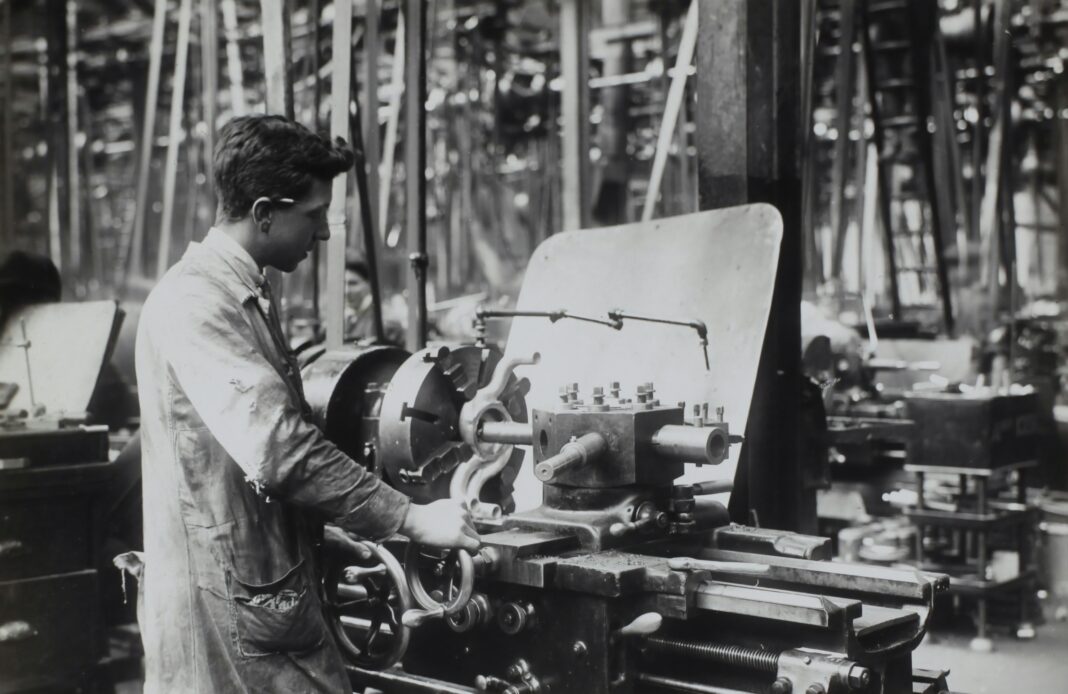

Image: Museums Victoria on Unsplash