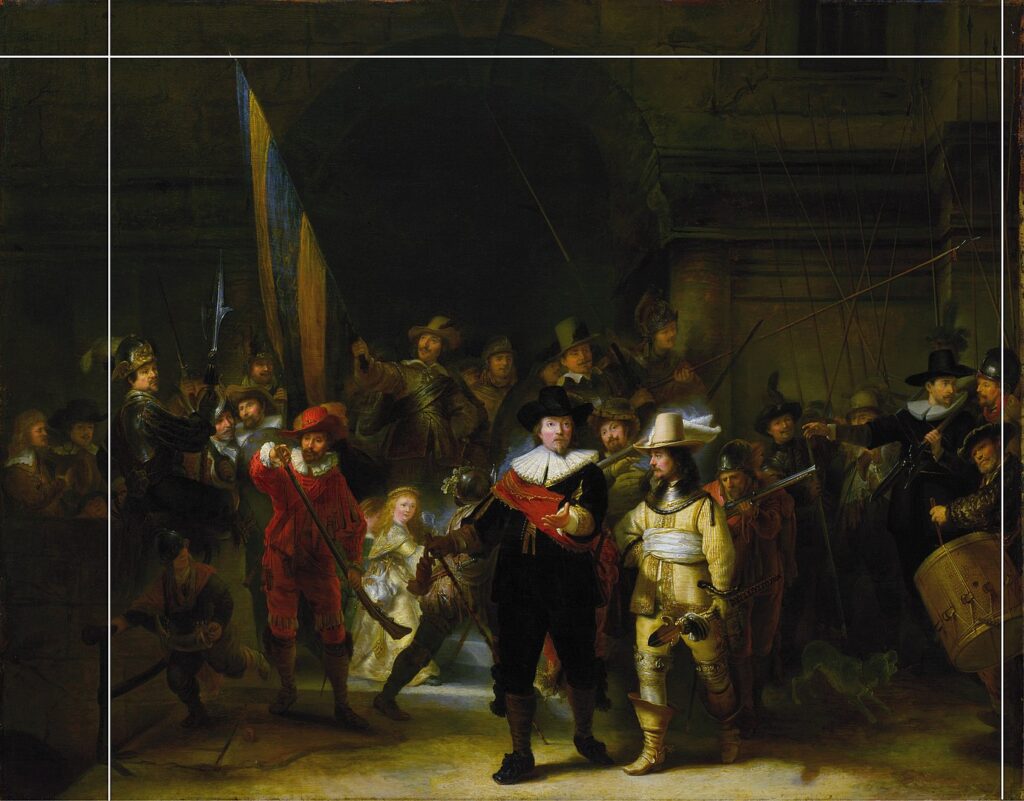

When you stare at The Night Watch, one of the most famous Dutch Golden Age paintings, you can feel something is missing. If you look closely at the borders, you will find truncated figures, and the reason is that the original canvas was actually trimmed! Almost a square meter of the original scene—including two persons, part of a bridge, and the back of a helmet—is missing.

For more than 300 years, the painting was exhibited without its original border—until now. The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has unveiled the missing part, as Rembrandt composed it, for the first time in 300 years.

But how could a portion of such an important artwork go missing? And how was the Rijksmuseum restoration team able to reconstruct it?

Let’s go back to the 17th century.

In 1639, the Mayor of Amsterdam, captain Frans Banninck Cocq, commissioned the painting to be exhibited in the town hall.

The painting’s original name was The Shooting Company of Frans Banninck Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch. In it, Rembrandt portrayed Banninck Cocq—the central and most illuminated figure—together with seventeen members of his civil militia guard.

When the painting was ready, it stayed at the Kloveniersdoelen, the headquarters of the Dutch civil guard. In 1715, catastrophe struck. Captain Banninck Cocq ordered the artwork to be placed in the town hall. But the painting was too big for the walls, so the border was trimmed on all four sides, and the “leftover” pieces were discarded.

The painting is indeed colossal: the portraits are almost human-sized. I was lucky enough to contemplate the three-and-a-half-meter high by more-than-four-meters wide masterpiece in the Rijksmuseum, in Amsterdam a couple of years ago.

After centuries of wars, vandalism, and restorations, it ended up being wrongly nicknamed The Night Watch, misinterpreting Rembrandt’s high-contrast style, or tenebrism, commonly used in Baroque paintings.

The painting indeed survived a lot of stress; it was even hidden in Maastricht’s caves during World War II. However, the trimmed portion was never found.

How science rescued a masterpiece from forgetfulness

Back in the seventeenth century, captain Banninck Cocq commissioned Gerrid Lundens to make a small copy of the painting. Obviously, Lunden’s copy was far from an exact replica. The style, colors, and even the proportions were different. However, people and objects missing from The Night Watch were there.

Scientists used Lunden’s copy as a cheat sheet to train artificial intelligence to visualize the missing part and reproduce it in Rembrandt’s style.

The algorithm worked in three steps.

The first neural network learned to recognize faces, bodies, and objects in Lunden’s version and reproduced them in the size of Rembrandt’s original composition. At this point, this reconstruction was still in Lunden’s style.

Then came the fine grain. Scientists cut a digitized version of the Rembrandt original into thousands of pieces for a second neural network to recognize the differences between Lunden’s and Rembrandt’s works in shapes and lines. A third one was used to identify the differences in colors and shadows.

After hundreds of thousands of iterations, the artificial intelligence reproduced the known part of Rembrandt’s original painting with high precision. At this stage, the computer was ready to paint the missing part—as if it were Rembrandt himself.

The complete artwork for the world to enjoy

The reconstruction team printed the missing part, guessed by the computer, and carefully added it to extend the original Rembrandt’s canvas. The completed masterpiece is now exhibited for a limited time—in all its glory—in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

It could be too expensive for many to visit Rembrandt’s masterpiece, but knowing that science can beautifully reconstruct our past is priceless.

References

- Rijksmuseum. (2021). Operation Night Watch.

- Anna Yesterday. (2019). The night watch, or The Shooting Company of Frans Banning Cocq and Willem van Ruytenburch.

Illustration by Dana Dumea

[…] Artificial Intelligence Learnt To Paint Like Rembrandt! […]